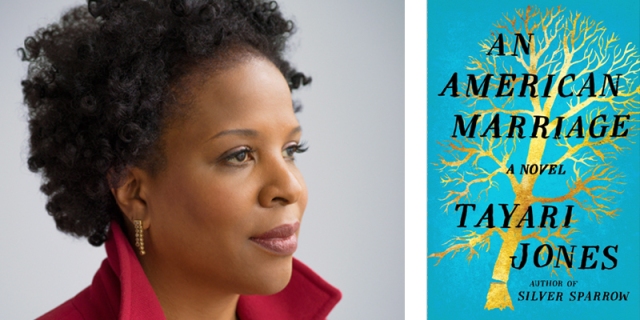

“There’s Nothing Virtuous About Finding Common Ground.” This was the headline for a recent article in Time magazine, penned by novelist and professor Tayari Jones (Emory). In her article Jones tells a compelling story about her upbringing. Her parents were activists, “veterans of the civil rights movement,” and under their tutelage she also learned to stand up for what she believed was right. On one occasion, riding in the back of a car for a zoo trip, she was astonished to discover that the driver was getting gas from Gulf, a company complicit in financing Apartheid. Young Tayari got out of the car and refused to ride further. She missed out on the zoo that day, but when her father came to collect her he was proud of her choice.

Jones uses her story as a launching pad to critique the desire for ‘common ground.’ She writes,

I find myself annoyed by the hand-wringing about how we need to find common ground. People ask how might we “meet in the middle,” as though this represents a safe, neutral and civilized space. This American fetishization of the moral middle is a misguided and dangerous cultural impulse.

Where was the ‘middle,’ she asks, with regard to American slavery? Where is the ‘middle’ with regard to Japanese internment during WWII? “What is halfway,” she queries, “between moral and immoral?” (The implied answer is ‘no place.’)

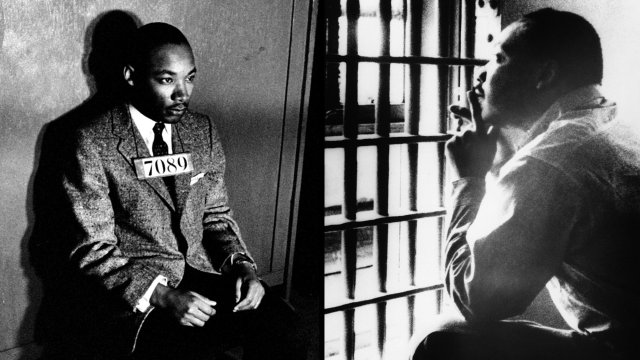

To be fair, I think Jones is right to critique the rhetoric of platitudes. There are times when appeals for ‘common ground’ are, as she suggests, rooted in “conflict avoidance and denial.” There are times when the language of ‘good people on both sides’ is a cheat, a deception, a statement intended to diffuse the perception of discomfort. In this I am reminded that when eight clergymen approached Martin Luther King Jr. and critiqued his methods of nonviolent resistance, he responded in his famous letter from the jail in Birmingham, “For years now I have heard the word ‘Wait!’ It rings in the ear of every Negro with piercing familiarity. This ‘Wait’ has almost always meant ‘Never.’ We must come to see, with one of our distinguished jurists, that ‘justice too long delayed is justice denied.’” Those clergyman didn’t want King to delay for the sake of compromise, they wanted him to delay because they were uncomfortable. They advocated for a kind of ‘common ground’ in order to ease their own discomfort.

And yet the blanket dismissal of compromise which Jones’s piece advocates is deeply troubling. Above all else, in the rejection of compromise there is a presumption that one side is completely right, while the other side is completely wrong. This might make sense when fighting Nazis in Germany, and it might have validity when defending yourself from an advancing army of cannibals, but things in real life are rarely so clear-cut. Furthermore, an appeal to no-compromise sounds compelling, and can effectively galvanize a base, but what if you find yourself on the outside of that base? It’s one thing to claim no compromise, as Jones does, with respect to issues of immigration, Black America, and White Nationalism, but what about no compromise on the part of abortion, or gender identity, or the dissolution of the family? Aren’t these also issues that display a spectrum of ‘moral and immoral’? Am I to reject compromise with Jones, or any other disputant, when a moral question is in play?

But there are deeper problems still. What has happened in the past when we have rejected compromise? Consider the following:

There are only two possibilities in Germany; do not imagine that the people will forever go with the middle party, the party of compromises; one day it will turn to those who have most consistently foretold the coming ruin and have sought to dissociate themselves from it. And that party is either the Left: and then God help us! for it will lead us to complete destruction – to Bolshevism, or else it is a party of the Right which at the last, when the people is in utter despair, when it has lost all its spirit and has no longer any faith in anything, is determined for its part ruthlessly to seize the reins of power – that is the beginning of resistance of which I spoke a few minutes ago. Here, too, there can be no compromise – there are only two possibilities: either victory of the Aryan, or annihilation of the Aryan and the victory of the Jew. (Adolf Hitler, 1922, emphasis added)

Here lies the real danger, to which Jones (unwittingly) points but to which both sides of the ideological debate are prone: the logic of Hitler applies to both sides of the ideological spectrum. And the grim truth is that if I determine you to be irredeemable—a misfit, a deplorable, recalcitrant, unwilling to change—then if I will not compromise with you I must do other things to you. In short, I open a door to the possibility of removing you from the equation. A refusal to compromise is the proto-rhetoric to murder. And if we aren’t planning to murder one another, then some form of compromise is going to be in order.

What is compromise? I can think of two definitions. First, compromise is the art of living within a complexity of differences. Every marriage is built on compromise. Two agents inhabit the same space but with different wills and desires. She wants to watch one film, he wants to watch another. Without compromise, how do you resolve the situation? Second, compromise is the art of disagreeing with someone without killing them. Sometimes a compromise is an agreement to disagree. Sometimes compromise means both of us giving up something we like for the sake of living in relative peace. And it’s worth noting that some compromises work, while others don’t. For example, the American government is founded on a “Great Compromise” which created our two houses of government (bridging the competing factors of states-rights and population). This compromise has been working successfully for hundreds of years. In the same vein, the Mason-Dixon line was a compromise with regard to the spread of slavery in early America—this was a compromise that failed, catastrophically.

For certain, it is not always the case that failed compromise ends in the murder of your disputant—some failed compromises end in divorce, or loss, or never speaking to one another again. But when we’re speaking of a political entity—such as a state—and when we are advocating through our rhetoric for a set of members in that state to be regarded as fundamentally immoral and irredeemable, then we are sidling up to a very dangerous line. Are there times when it is the right thing to do away with an ideological bloc? Certainly. Can we kill Nazis with impunity? Sometimes. Have we found a better way, in the past 2000 years, of changing someone’s mind than violence? The answer is uncertain—gulags and re-education camps are some of the 20th century’s greatest horrors. The only way, it seems, of changing someone’s mind without violence is, well, compromise. Finding common ground, highlighting the good ‘on the other side,’ and patiently, sometimes painfully, waiting while working for change. The alternative is to murder them.