When I wrote last week about Love and Relationship I had no real intention to follow up that post. There were (and still are) things to say about defining terms like “progressive theology,” and there’s something to say about progressive revelation. But this week I encountered another example of progressive logic that startled me so much I felt the need to spend some time with it. It is the idea that Traditional Christian teaching on sexuality is in some sense the cause of sexual dysfunction. The more I think about it, the more I think it identifies another feature of progressive theology that we’ve got to try and dissect.

If you’ve been reading the news, then you know that there has been a series of massive, deeply disturbing revelations about sexual abuse and cover-up in the Catholic church. Responses have been grieved, frustrated, and angry, and in the midst of this all there is a strong desire to explain or rationalize the goings on. One piece, produced in part by the scandal, was from Rod Dreher, author of The Benedict Option and chief editor of the journal The American Conservative. He published a story and interview with a man named Gabe Giella, a gay, former Catholic, former seminarian, who recounts some of his horrifying experiences in seminary. (Long story short: the seminary was full of sexually deviant individuals, and when he didn’t play along, he was the one who got removed.) The article is worth reading in whole, and I recommend it strongly, but the key paragraph that startled me is the following. Giella writes,

Sexual secrecy is the currency in the church and learning how to use it is almost treated like an art form in seminaries. This culture has been woven into the fabric of Roman Catholic clergy culture for centuries. The church’s strict and absolute regulations around sex and sexuality which themselves are created and promulgated by the very men who breach them provide a perfect cover for those whose own sense of sexuality is without boundaries, regulation, or integration. Sexual secrecy and blackmail is the clergy’s bitcoin by which position, power, and control are bartered in the shadows, costing children and adults alike their faith, their safety and well being — and in some cases, their lives.

Now, before I comment on this, I want to make something really clear. My intention today is not to reflect upon Catholic practice and faith. As a rule, I keep my commentary on current events to those issues with which I have some personal involvement—I blog about conservative evangelicals, and I largely leave the issues of Orthodox, Catholic, or other believers to themselves. I think that’s only fair, and today’s post is really no different. I am not commenting, chiefly, on the Catholic sex abuse scandal. Serious commentary, and the business of criticizing and proposing solutions to that problem, is the purview of faithful Catholics (who, I add, have their work cut out for them and need our prayers). But in the comments I read from Giella, I detected elements of progressive thinking that I’ve encountered much more broadly. It is those elements that I want to treat with now.

Yeah, but what about smelling evil?

First, there are a few things that Giella says that are quite important for us to hear. Chief among them is the role that secrecy plays in situations like the one he encounters. Secrecy gives added, corrupting power to sin, and in a context like a Catholic seminary, the secrecy of sexual desire—especially same-sex desire—must be necessarily strong. The wicked danger of this, however, is not simply that men keep quiet about their sexual struggles, but rather that secrecy is utilized as a tool of further suppression. And it certainly seems that in some circumstances suppression of talk about a situation is regarded as a solution to the problem, so that if we don’t talk about the elephant in the room, perhaps it will go away.

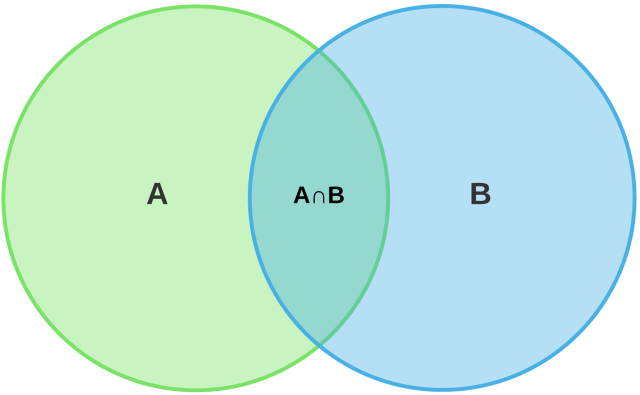

Another critically important aspect of Giella’s comments is his separation of gay priests from pedophile priests. Clearly, in the Venn diagram of these categories, they are not the same thing. There are gay men who are not pedophiles, and there are pedophiles who are not gay. Giella, and the other progressive thinkers I am familiar with, are right to reject the false equivalency that many traditional Protestants hold with regard to these categories. One does not necessarily mean the other.

Giella is not the only person who I’ve encountered recently who stresses this distinction, and he and the others I’ve read press it even further. They reject any material link whatsoever between desire for homosexual sex, and desire for homosexual sex with boys. For them, it is not a Venn diagram at all, with an overlap of homosexual and pedophile priests, but rather two completely separated circles, reflecting two completely different types of individuals. This makes a kind of sense, if one of your fundamental presuppositions is that homosexual attraction is a good. To the degree that you are committed to that claim, you must consequently reject any association between homosexual desire and categories of deviant desire (of which pedophilia would be one).

Since (on this line of thinking) deviant sexual desires cannot, by definition, account for homosexual and pedophiliac priests, something else must account for this. It is this ‘something else’ that I’ve detected in Giella’s rhetoric, namely, that the tradition itself is somehow responsible for creating this situation. Consider one of his sentences again, “The church’s strict and absolute regulations around sex and sexuality which themselves are created and promulgated by the very men who breach them provide a perfect cover for those whose own sense of sexuality is without boundaries, regulation, or integration.” The language of ‘integration’ is loaded. Earlier in Giella’s piece he speaks about integrated sexuality, which means, effectively, living openly as an ‘out’ individual. And the suggestion, however subtle, is that somehow it is the Church’s traditional, outdated, and repressive teaching on sexuality that is the real cause of the sex abuse scandals.

Rev. Krzysztof Charamsa, left, and his boyfriend Eduard. He has lost his position in the Vatican. One also wants to ask, How can ‘integration’ be complete when you must also deny your vows? Isn’t there a disintegration at play as well? The presumption is that living ‘out’ is more honest, even if it means committing perjury.

Think about this further. If ‘secrecy’ has created a climate of sexual sin, then what better way to address that secrecy than living openly, or ‘out’? The solution hinted at is that if the Church were to update its teaching on sexual morality, these problems would go away.

This, it seems to me, taps into a foundational aspect of Progressive theology—chiefly, and even embedded into the name, the aspect of progress. The logic runs something like this: we know more about sexuality than any time in history. Our knowledge, not surprisingly, exceeds that of the New Testament authors, who were entrenched in their first century worldview. Consequently, our new knowledge demands a re-thinking of those old (i.e., outmoded) sexual ethics. We have matured out of our old cultural taboos, and now we know that homosexual desire is not only not an evil, but a positive relational good. Our teaching must be adjusted accordingly.

Here’s the twist, though. Adherence to the old teaching is not only backwards and anti-progress, it is also dehumanizing. If I proclaim a traditional Christian sexual ethic, which condemns all homosexual practice, then I might be participating in a kind of abuse. My teaching is contributing to the fracturing of personalities, to the denial of central humanity, and even (on some accounts) to increased suicide. This, to me, explains why many of the Progressive Christians I’ve encountered view their teaching as a kind of liberation. They are ‘releasing’ people from the strictures of tradition to live full, ‘integrated’ lives.

Human flourishing, in other words, cannot exist without sexual freedom.

There is so much to say at this point that I despair of saying it all. I think I will try to say only three things. First, I reject wholesale the narrative of ‘progress.’ Since the time of the Enlightenment, it has been a common enough (and false) claim that our new knowledge is superior in every way to the knowledge found in Christian teaching. It was there that the beginnings of the science and religion debate began to take shape. Heady with new scientific discoveries, Enlightenment thinkers readily dismissed the whole of Christian teaching, or even re-edited it to meet their specifications. They were guilty, then as now, of what C.S. Lewis called “chronological snobbery.” They didn’t evaluate the old ways of thinking on their own terms—instead, they were prejudiced toward their present and weighted the scales unfairly toward the past. New is not always better. With regard to modern sexual ethics, it is worth noting just how new they are in the history of the human race. Whatever claims they make to scientific basis and universality, these are fundamentally untested theories.

Second, there is something wrong, and even dishonest, about the rejection of categories of ‘disorder’ when discussing homosexual desire. On a biological, even evolutionary account, the purpose of sexual desire is the creation of more members of our species. To do that requires one member of each gender—sperm and egg. It follows that same-sex attraction, if we start with an evolutionary biological account of the human, is an obvious deviation from the norm. It reflects a disordered desire on the part of the individual. I want what I ought not to want as a sexual human being. To turn and sanctify the disorder does not and can not bring the person to greater integration. Instead, it reflects a kind of sanctified nihilism where this world, and its desires, and a form of temporal happiness, are all that matters. That, to me, is anti-Christianity.

Finally—and while this is the most important argument for me it may seem like the weakest—I have faith in the Spirit of God that He has not deceived us in the Scriptures brought down to us. Granted, there are crucial differences between the ancient world and our modern one. Granted, there are commandments and practices which appear to have lost the sting which binds them to us (e.g., women with head coverings, casting lots, etc.). But the Scripture presents a picture of the human person which has not changed—that I, and you, are made in the Image and likeness of God, that there are desires within my body that war against my living out of that image, that I am commanded to resist and submit those very desires to God’s Spirit in obedience, and that obedience looks a great deal like crucifixion of the self.

St Anthony, patron of those who resist the World, the Flesh, and the Devil.

Here, as with last week, it hasn’t really been my intention to argue with the line of Progressive Theology that I’ve encountered. In both cases, my goal has been to try and single out and bring a degree of clarity to an element of what is an admittedly large and complex body of thought. A proper argument against Progressive Theology, as I see it, would require a far more robust analysis of the concept of ‘progress,’ and with that a commensurate discussion on the role and sources of authority.

I could make my peace with Willow Creek because I used to know what was wrong with it. Not anymore. Just a few months ago news began to break about some serious allegations regarding Bill Hybels, Willow’s founding and senior pastor, leadership guru and megachurch patriarch. First in the

I could make my peace with Willow Creek because I used to know what was wrong with it. Not anymore. Just a few months ago news began to break about some serious allegations regarding Bill Hybels, Willow’s founding and senior pastor, leadership guru and megachurch patriarch. First in the