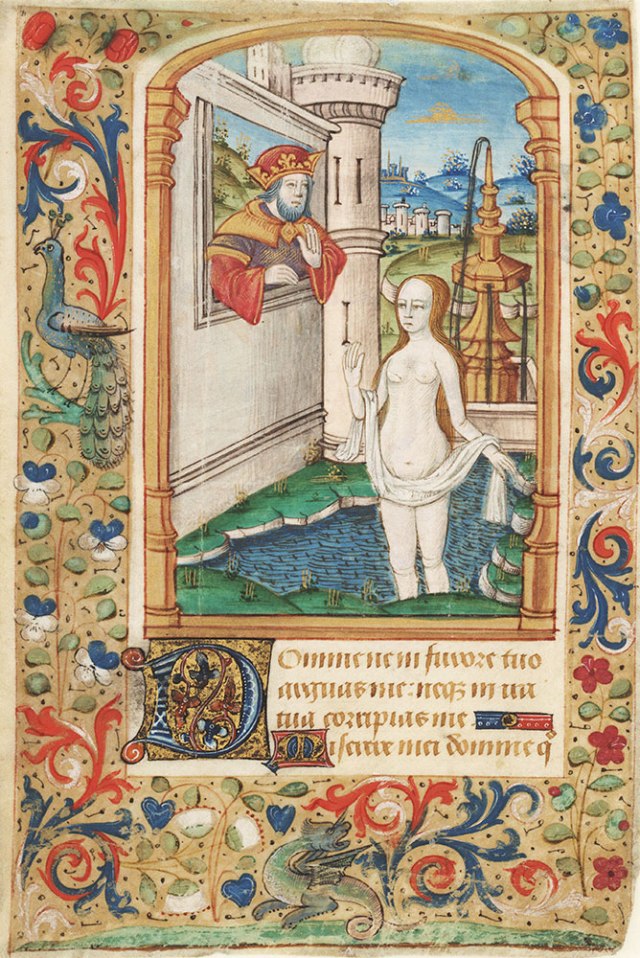

This week, the flagship magazine of Evangelicalism, Christianity Today, published an article by Kyle Worley on the importance of acknowledging the rape of Bathsheba. The episode recounted in 2 Samuel 11, in other words, does not merely document an account of adultery and murder, but should be labeled for what it really is: the rape of an innocent woman by a man in power. “The story of David and Bathsheba,” Worley writes, “is not a story of adultery or an affair, but one where a powerful man is sexually exploiting a vulnerable woman and is willing to use coercive power to call her to his chamber and cover up his actions.” Worley goes on to suggest that Evangelical resistance to admitting David’s rape betrays an unwillingness to acknowledge systemic abuses of power: “I’m convinced that we don’t want David to be a rapist because we don’t want to reckon with the sin of abusive power.”

Bathsheba, by Jean-Léon Gérôme

The article is troubling—it suggests that if I have a resistance to accepting his interpretation (of rape), it is because I have a deeper problem (I refuse to admit abusive power). This, I think, amounts to a bit of intellectual bullying. More than this, however, the article insufficiently accounts for the messy modern dialogue about sex in the Bible, and the easy, if not cavalier way that modern categories of judgment are given interpretive priority over ancient texts—i.e., how a ‘woke’ exegesis can be a distorting one. Ultimately, the article is tone-deaf to the way that a modern label such as ‘rape’ can further distance us from fully acknowledging the power-sins that—I fully agree—are at the heart of the story of David’s sin. The result is that Worley gets it half wrong, and half right, but in the process the wrong makes a mess of whatever good might have come from the right.

We will need to begin by talking about rape. The word itself is potent, violent, evocative, and fearful. It can be ‘triggering’ in that even its utterance evokes in victims the memory of abuse. But this supra-powerful nature of the word is very the place to begin to ask questions. Rape, like the word ‘racist,’ has in our present age become a power-label, not dissimilar to ‘bourgeoisie’ in Communist Russia, or like ‘privileged’ is sometimes used today. Each word, of course, has a definite meaning, but in its cultural context it is invested with additional performative power. They are words that can do things to people. In practice, a given power word in the mouth of a victim levels the playing field. You have done X to me (whatever X might be) and in order to equalize the situation I will label you accordingly. If the label sticks, no fact-finding or investigation is necessary; if I can label you, I can destroy you. Ironically, each word—duly invested by a cultural narrative—has the potential to become its own abuse of power.

“Struggle Sessions” in Maoist China were public humiliations performed against citizens accused of, among other things, thought crimes.

Viewed from this perspective, I might well object to labeling David’s sin with Bathsheba as ‘rape’ in the same way that I would object to labeling Solomon’s acquisition of wealth as ‘bourgeoisie.’ In both cases I would be applying a highly contextualized modern power-word to an ancient context. I am executing a ‘woke’ exegesis on an ancient text, and whatever I gain is likely to come at the expense of important things in the text itself. I would feel quite similarly if I encountered an article asking, “Did David mis-gender Mephibosheth?” The ‘woke’ questions we ask, and the narrative, do not so easily align.

Worley consciously links David’s sin to abuse of power (again, I think this is correct), but neglecting the broader cultural context of our discussion about consent, sex, and gender in the modern world means that he also—subconsciously I am sure—imports an unhappy logical correlative. All rape, Worley’s article suggests, is abuse of power, and on this basis he claims that “the story of David and Bathsheba appears to many modern readers, including me, to meet contemporary definitions of rape.” While it is doubtless that all non-consensual sexual encounters involve some abuse of power, the dynamic between the two categories (sex and power) remains unclear. As a result, it seems that contemporary definitions of rape depend, in part, on an inversion of the initial logic: “all rape is abuse of power” becomes “all abuse of power is rape.” This inversion brings about significant effects—clear conditions of violence are exchanged for fuzzy conditions of power. In turn, the inversion plays into the inherent flexibility of power-words—any situation in which an individual feels personally compromised by the power of an authority can be labeled ‘rape.’ This creates confusion and fear, and while it offers a heady cultural critique of power (down with the bourgeoisie!) it does nothing to help us understand how to manage or shape it. It is a mis-labeling. Ironically enough, it violates the person in power in an unwarranted way.

Marc Chagall’s interpretation of David and Bathsheba.

This brings us back to David. Did David rape Bathsheba? The text doesn’t say, and depending on your convictions about the nature of the text, that may be a pretty strong argument. Furthermore, it is worth noting that, compared to the other episodes of rape in the Bible (Dinah in Genesis 34 and Tamar in 2 Sam 13), David’s encounter with Bathsheba looks very little like these—specifically in the fact that these episodes document the lust of the male perpetrator, the unwillingness of the female victim, the violence of the act itself, and the grim consequences for the perpetrator(s). Instead, David sees Bathsheba, calls her over, and they have sex. There is certainly a power dynamic involved here—David is the most powerful man in the kingdom. But—once again—the modern language of consent does not easily square with the ancient world. Do ancient husbands and wives communicate permission to one another? What rights are given to ancient kings with reference to the property of their subjects? On these issues we are speculating.

If we can speculate about the unarticulated motives of David, then we can speculate about Bathsheba’s unarticulated motives as well. What was she doing, bathing on the roof? Did she know David would be walking past? These questions have, similarly, led to some unfortunate interpretations. Let me be extremely clear—any exegesis that argues that Bathsheba, by being scantily clad, brought this on herself should be rejected outright. The point to highlight is that once again the motives of the characters are unspoken in the text. Do we have other texts that inform our thinking about Bathsheba as well? Curiously, in 1 Kings 1, under instruction from Nathan, she helps to arrange matters politically so that Solomon becomes king instead of Adonijah. How we interpret her motives will depend on how much charity we are willing to extend to her. Is Bathsheba simply saving her own life and the life of her son? Is she merely obeying the advice of David’s court? Or, more maliciously, has this been Bathsheba’s plan all along? It would not be challenging to cast her in the role as the conniving female, working her way to the queenship of Israel by means of the powerful men around her. I think this is a bad interpretation, but it suggests that we have as much evidence to accuse Bathsheba of social climbing as we do to accuse David of rape.

Susan Hayward, smouldering as Bathsheba. It is worth noting that most images of Bathsheba highlight her sexiness while avoiding David’s gaze. Is there something to be said for how we only re-create David’s gaze by participating in it?

What, then, was the nature of David’s sin? Worley’s article rightly notes that Nathaniel, when he calls David out for his sin, critiques David’s abuse of power. But a critically missing component is the opening verses of 2 Sam 11: “In the springtime, when the kings go off to war, David sent Joab…” David is a king, David should be at war, but he’s not. The sin of David begins here, in a changed relationship to his kingship. Instead of performing the duties of a king, David is—what?—enjoying his kingdom? The text will go on to show how he enjoys it disastrously. Not only does he treat another man’s wife as part of the property of his kingdom, he then covers up his indiscretion by arranging to have the husband murdered, then marries the widow. Nathaniel doesn’t accuse David of rape—he accuses him of theft.

Charles Williams

Importantly, the interpretive frame for understanding the David/Bathsheba episode is David’s relationship to his own kingdom. Charles Williams, Inkling and Arthurian poet, captures this dynamic in a phrase he uses to describe the beginning of King Arthur’s demise. Arthur, looking out over his people, asks himself a question: “the king made for the kingdom, or the kingdom made for the king?” Do I exist to serve others, or do others—all that I see—exist to serve me? In that moment, Arthur’s relationship to what is good is corrupted—it constitutes his ‘fall’. Instead of perceiving his power as a tool to benefit the people, now the people benefit his power. David’s sin is the same.

It also seems clear from the text that David didn’t learn his lesson from the episode with Uriah/Bathsheba. In 2 Sam 24 we learn that David is tempted to take a census of Israel. The text is frustratingly silent on what David thought he would gain from counting the Israelites—whether he wanted to know his military strength, or had a new tax plan—all we know is that it represented an act of disobedience. He viewed his people as existing for his plans, rather than seeing that he, as king, existed to serve Yahweh’s plans for Israel. The result was a confrontation with another prophet (Gad, this time) who communicated three options. David must choose: seven years of famine, three months of flight before enemies, or three days of pestilence. We should note, here, that two of these options effect the economics of Israel, and one impacts David personally. David chooses the pestilence, “Let us now fall into the hand of the Lord for His mercies are great, but do not let me fall into the hand of man.” But after the plague reaches Jerusalem David recognizes his error and changes his prayer, “Behold, it is I who have sinned, and it is I who have done wrong; but these sheep, what have they done? Please let Your hand be against me and against my father’s house.” Let me suffer—as the king—and not my people. This is how David had to learn that the kingdom didn’t exist for his benefit. This is how David is shaped with respect to his power and authority.

It seems to me that all three sins—the sin of adultery, of murder, and the sin of the census—are, in the text, fundamentally the same sin. Each points to David’s misuse of his kingly power, each seems to lie in the idea of the king as possessing a kind of sovereign ownership over his people, and each demands repentance and re-learning on his part. It also seems to me that, unless we are willing to call the census a ‘rape’ (i.e., all abuse of power is rape), or the murder a ‘rape’, then we ought to be quite careful in labeling the sin with Bathsheba ‘rape.’ I want to point out a further reason for this. Christianity, as a rule, has been beset by three categories of sin in leadership: sins of sex, money, and power. Trenchantly, we seem to focus on sex and money while neglecting sins of power. When a minister has a fall from grace, it is far more often because of adultery or financial misuse than ever because the minster abused his ministerial authority. We struggle even to see the sins of power. In view of this, forcing our interpretation to incorporate a modern definition of rape may be fundamentally counterproductive to the message of the text. If we’re going to see the sin of power, we must see it in all its effect in the text, as it impacts men and women alike.

It seems to me that all three sins—the sin of adultery, of murder, and the sin of the census—are, in the text, fundamentally the same sin. Each points to David’s misuse of his kingly power, each seems to lie in the idea of the king as possessing a kind of sovereign ownership over his people, and each demands repentance and re-learning on his part. It also seems to me that, unless we are willing to call the census a ‘rape’ (i.e., all abuse of power is rape), or the murder a ‘rape’, then we ought to be quite careful in labeling the sin with Bathsheba ‘rape.’ I want to point out a further reason for this. Christianity, as a rule, has been beset by three categories of sin in leadership: sins of sex, money, and power. Trenchantly, we seem to focus on sex and money while neglecting sins of power. When a minister has a fall from grace, it is far more often because of adultery or financial misuse than ever because the minster abused his ministerial authority. We struggle even to see the sins of power. In view of this, forcing our interpretation to incorporate a modern definition of rape may be fundamentally counterproductive to the message of the text. If we’re going to see the sin of power, we must see it in all its effect in the text, as it impacts men and women alike.

If we mean to draw from David’s life a critique of the use of kingly power and authority—which we should very much indeed do—then we might want to reconsider the use of power-words, prone to their own abuses of power, in identifying these factors. The narratives—our modern sexual narrative and the Biblical power narrative—are not so easily intermingled as we might hope, and uncritical cross-pollination between them creates harm in our interpretation of the text.

I could make my peace with Willow Creek because I used to know what was wrong with it. Not anymore. Just a few months ago news began to break about some serious allegations regarding Bill Hybels, Willow’s founding and senior pastor, leadership guru and megachurch patriarch. First in the

I could make my peace with Willow Creek because I used to know what was wrong with it. Not anymore. Just a few months ago news began to break about some serious allegations regarding Bill Hybels, Willow’s founding and senior pastor, leadership guru and megachurch patriarch. First in the